When you write a novel, there’s one query you get very used to responding to: “What’s it about?” My answer sounds more like a question. “The Brontës?” I say, looking for a smile of recognition. This is often forthcoming from women, much more rarely from men. People tell me they love Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights and ask if my book is about Charlotte or Emily. “Actually,” I tell them. “My main Brontë characters are the other two—Branwell and Anne.”

But Anne, who wrote the quieter Agnes Grey, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, a novel that shocked on its publication, has often been unfairly overlooked. It is a cruel irony that, with the Brontë Parsonage Museum celebrating the bicentenaries of the births of each of the siblings over the last few years, 2020, the year of Anne, has seen an unprecedented closure of the house due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

When you write a novel, there’s one query you get very used to responding to: “What’s it about?” My answer sounds more like a question. “The Brontës?” I say, looking for a smile of recognition. This is often forthcoming from women, much more rarely from men. People tell me they love Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights and ask if my book is about Charlotte or Emily. “Actually,” I tell them. “My main Brontë characters are the other two—Branwell and Anne.” [...]

I had always loved the writings of all three Brontë sisters, and been fascinated by their strange romantic story—the litany of tragic deaths, the elaborate playworlds the siblings created together, and the fact that, as women writers, they chose to adopt male pen names, Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. I studied for a Master’s in nineteenth-century literature at the University of Oxford, and Charlotte Brontë was one of the writers I focused on. But it was in 2016, when reading the first biography of Charlotte, published in 1857 by fellow Victorian novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, that I came across a new, tantalizing story about the Bronte family.

Like their characters Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey, Charlotte and Anne Brontë both worked as governesses, one of the few professions open to women of their class and education level. In May 1840, Anne took a position teaching the daughters of the Robinson family at Thorp Green Hall, a house near the villages of Great and Little Ouseburn. Branwell joined her a little under three years later to act as the son’s tutor.

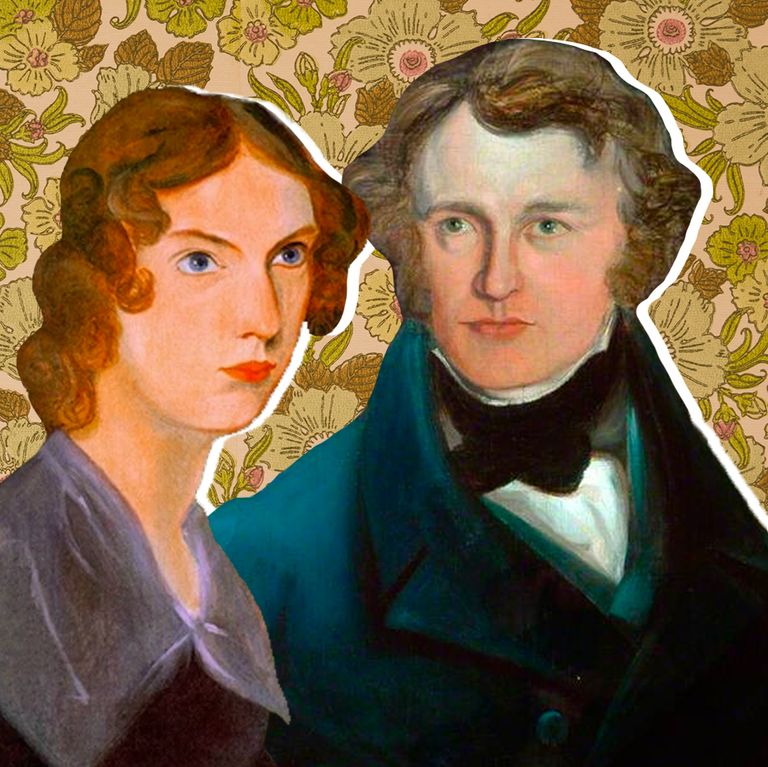

It was here that he met the mistress of the household, Lydia Robinson, the woman Mrs. Gaskell eviscerates in a scathing section of her biography—and my novel, Brontë's Mistress, finds its inspiration.

Gaskell described Lydia as “profligate.” She wrote that this married woman in her forties had “tempted” twenty-five-year-old Branwell into engaging in an affair with her, and that “in this case the man became the victim.” She even suggested that Lydia was responsible for Branwell’s addictions and illness and, indirectly, his death and those of his celebrated sisters. So damning was the character assassination that Lydia threatened to sue Gaskell for libel, leading to her retraction of the allegations.

I was fascinated and began my research in a whirlwind. I knew that this was a story I had to write. What had really happened between Branwell and Lydia at Thorp Green Hall? What part had Anne played in any illicit romance? From the very beginning, I felt there was a novel here, one about a woman very different from Charlotte Brontë's protagonists, who are typically poor, plain, young and virginal. Lydia Robinson was wealthy, beautiful, older, and sexually experienced. But she was still a woman in the nineteenth century, and as such she had few choices open to her.

After my initial rush of inspiration, I used all the skills I’d developed through my academic studies to be methodical in my research. I read many Brontë biographies and journal articles. I created spreadsheets of all known dates in Lydia’s life and the lives of the Brontës. I consulted digitized census records to understand the servants who were part of the Thorp Green Hall household and the families they had back home. I corresponded with archivists to learn more about members of the York Medical Society, and librarians to track down poems by long-forgotten country curates. I may have been living in twenty-first century New York City, but for around a year I might as well have been living in 1840s Yorkshire.

When I finally began writing the novel, I held myself to a high standard of accuracy. We can never know for certain what historical figures thought, felt, or said to each other, but I wanted everything that happens in my novel to be something that could have happened.

(Read more)

0 comments:

Post a Comment